How to tackle low labour utilisation in South Africa

South Africa’s stubbornly low labour utilisation rate[i] is an international outlier and an impediment to realising oft-stated policy aspirations of improving economic growth and reducing inequality.[ii] At a macroeconomic level, it also inhibits fiscal and monetary policies in supporting stabilisation and long-run growth.

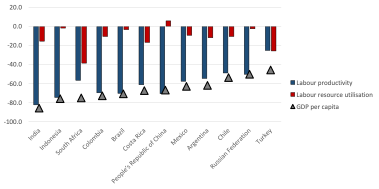

The low level of economic activity of South Africa’s working-age population has a large cost. Compared to countries with similar labour productivity levels, South Africa’s GDP per capita is much lower, simply because these others employ more of the working-age population (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Countries covered in the OECD’s Going for Growth exhibit large variation in GDP per capita (compared with the upper half of OECD countries, 2018)[iii]

Source: OECD. 2019. ‘Economic policy reforms 2019: going for growth’

In this article, we summarise the findings from our paper, Addressing low labour utilisation in South Africa.[iv] This paper considers South Africa’s labour markets against a range of theoretical models, discusses the drivers of a low labour utilisation rate, assesses the impact of labour market policies, and presents solutions based on policies from countries that have achieved a significant increase in labour utilisation.

Drivers of weak labour utilisation

Low labour utilisation in South Africa is the result of several factors, many of which stem from the apartheid regime. These include:

- Exceptionally high youth unemployment, mainly as a result of weak education outcomes and low labour absorption.

- The geographic distribution of the population, a large portion of which is located far away from available jobs, with limited affordable transport and housing options. This occurs both within cities and across provinces, with large variations in economic activity and unemployment across areas.

- A wage bargaining system that privileges insiders (those currently employed and larger firms able to pass on wage costs) at the expense of outsiders (the unemployed, young work-seekers, and smaller firms less able to afford high wages). Collective bargaining is insufficiently flexible, with industry level agreements legally extended to all firms and unable to set real wages to clear the labour market.

- Under-resourced public employment services that fail to reach unemployed workers with limited means.

- Complex regulations, high market concentration, cumbersome licensing and permits, and poor network services, which dampen competition and reduce the labour intensity of economic activity.

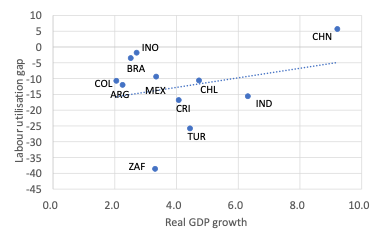

South Africa’s economic growth rate has remained low over the past decade, and higher sustained growth would certainly increase employment. However, Figure 2 shows that other countries with similarly low trend growth have much higher utilisation rates. This implies that other factors need to be addressed alongside growth constraints in order to raise employment meaningfully.

Figure 2: Average GDP growth and labour utilisation

Source: OECD Economic Outlook Database and OECD. 2019. ‘Economic policy reforms 2019: going for growth’

Notes: ARG: Argentina; BRA: Brazil; CHL: Chile; CHN: China; COL: Colombia; CRI: Costa Rica; IND: India; INO: Indonesia; MEX: Mexico; TUR: Turkey; ZAF: South Africa.

South Africa’s labour policies over the past decade

In general, poorly designed labour market regulations are well understood as major obstacles to employment creation. Many in South Africa deviate from global best practice. One example is the introduction of amendments to the Labour Relations Act in 2015, which aimed to protect temporary workers but lowered temporary work durations to well below optimal levels identified in the National Development Plan. Similar challenges lie in employment equity and black economic empowerment policies, which have improved representation of disadvantaged groups but their overall impact on labour utilisation has been negative.

The employment tax incentive (ETI) is an outlier among these policies, both because it directly supports higher labour utilisation and because data is available to assess its impact. The ETI was introduced in 2011 as a firm-level subsidy to increase labour demand. Overall, studies to date suggest that quite a high level of jobs are supported by the incentive, but the number of new jobs created remains low, perhaps due to insufficient complementary policies or targeting.

Policy recommendations

Increasing labour utilisation in South Africa requires a complete rethink of the current approach to employment creation, in particular by reducing “insider” effects of regulations and other practices that keep the unemployed out of work. Arguably the most urgent, and probably the most accessible, intervention to get more employment growth in the short term is to improve the transition from school to jobs, by increasing in-work training and industry involvement. Entry into the labour market could be facilitated by expanding the currently minimal public support services to improve matching, provide qualification and offer mobility support. Germany provides useful lessons from its early-2000s reform of its public employment service and successful vocational education and training system.

Our international review and local evidence suggest that reducing regional economic disparities and the gender gap can increase labour utilisation rates. South Africa can learn from the European Union’s regional funding mechanisms and support for female workers. The OECD’s recommendations to improve traditional settlement areas may help South Africa reduce mobility costs.[v]

As shown in our paper, a high unemployment rate and low labour utilisation are outcomes of the kind of wage-bargaining process South Africa has. One method for optimising labour use is through negotiated, high-level social accords,[vi] which hold down labour-cost growth rates to raise investment and job creation. Most instances of the successful use of social accords occur in high-income countries such as Austria and Scandinavia. Such accords are far less commonly used in developing and emerging economies.

South Africa’s post-apartheid policy set emphasises fair treatment and compensation of employed workers, but the unintended consequences of this approach have been ignored. The outcomes for relatively high-skilled unionised and formal sector workers have been positive, while reducing demand for less-skilled workers and leaving many workers in more precarious positions. Both firing and hiring costs need to be lowered further, as completed in important labour market reforms enacted in Italy. In addition, black economic empowerment and employment equity policies need to be reviewed and redesigned to lower their costs to the economy and enable better outcomes for unemployed South Africans.

Supportive microeconomic reforms are key to addressing South Africa’s unemployment problem. The importance of competition has been highlighted in most OECD Economic Surveys of South Africa. The first survey in 2008 highlighted the entry barriers for foreign firms, the role of state ownership and intervention, and the excessive administrative burden which hinders business growth and the development of small, micro, and medium-sized enterprises.[vii] Other surveys continued to highlight problems with product market reforms, and yet progress in addressing these reforms has been slow. Industrial and other microeconomic policies also have an important role to play in supporting higher labour utilisation, especially in South Africa where they mainly support highly capital-intensive sectors.

Conclusion

South Africa is an outlier among emerging economies because of its relatively low productivity gap and high labour utilisation gap (compared with advanced economies). Creating many more jobs for less skilled workers is an achievable target, as demonstrated by other countries, and will go far in raising overall output and income and reducing inequality.[viii] The factors and recommendations discussed in this article are not new but remain critical to sustainably increasing employment and GDP per capita in the country.

Notes

[i] A productivity gap measures how far a country is from the global productivity frontier. A labour utilisation gap measures how much labour is being used per working-age adult relative to other economies.

[ii] National Planning Commission. 2013. National Development Plan 2030. https://www.gov.za/issues/national-development-plan-2030.

[iii] Labour productivity is measured as GDP per hour worked. Labour resource utilisation is measured as the total number of hours worked over the population aged 15-74. The comparison is based on the weighted average using population weights of the 18 OECD countries with highest GDP per capita in 2018 based on 2018 purchasing power parities. The sum of the percentage difference in labour resource utilisation and labour productivity does not add up exactly to the GDP per capita difference since the decomposition is multiplicative.

[iv] Loewald, C, Makrelov, K and Wörgötter, W. 2023. ‘Addressing low labour utilisation in South Africa’, in Unlocking growth prospects in post-pandemic South Africa, edited by C Loewald and M Stern. Pretoria: South African Reserve Bank: 44–79.

[v] OECD. 2019. ‘Linking indigenous communities with regional development’. OECD Rural Policy Reviews.

[vi] Nattrass, N. 2004. ‘Unemployment and AIDS: the social‐democratic challenge for South Africa’. Development Southern Africa 21(1): 87–108.

[vii] OECD. 2008. ‘OECD territorial reviews: The Cape Town City-Region, South Africa 2008’.

[viii] Anand, R, Kothari, S and Kumar, N. 2016. ‘South Africa: labor market dynamics

and inequality’. IMF Working Paper No. 2016/137.

Download article

Post a commentary

This comment facility is intended for considered commentaries to stimulate substantive debate. Comments may be screened by an editor before they appear online. To comment one must be registered and logged in.

This comment facility is intended for considered commentaries to stimulate substantive debate. Comments may be screened by an editor before they appear online. Please view "Submitting a commentary" for more information.